Burnout or Perimenopause?

Fatigue, brain fog or burnout in your 40s? Learn how perimenopause can reduce resilience and amplify stress — and why recovery may feel harder now.

Perimenopause can look like fatigue.

It can also look like brain fog, poor sleep, irritability, anxiety, low mood, weight changes, loss of motivation, or a heavy, sluggish feeling in the body.

In other words, it can look exactly like what many women are told is burnout.

This symptom overlap is one of the main reasons perimenopause is often missed or mislabelled as burnout — by women themselves and sometimes by healthcare providers.

When burnout is part of the picture — but not the whole story

For many women, work really is demanding.

Long hours, responsibility, emotional labour, and sustained mental load can lead to genuine work-related burnout. Acknowledging this matters.

At the same time, many women notice that their ability to cope has changed.

Stress feels heavier. Recovery takes longer. Things that were once manageable suddenly aren’t.

This often leads to questions like:

Why does work affect me more than it used to?

Why does burnout feel deeper or harder to recover from this time?

Questions many women begin asking

As fatigue and emotional depletion persist, many women start to wonder:

Could I be burned out from work — but also physically less resilient than before?

Has something changed in my body that makes stress hit harder now?

Is there something underneath this fatigue that isn’t only related to my work environment?

These questions don’t deny burnout. They reflect a sense that the full picture hasn’t yet been explored.

Where perimenopause fits in

Perimenopause is a hormonal transition phase that can begin years before menopause, often while menstrual cycles are still regular.

For many women, symptoms start in the early to mid-40s, though they can appear earlier. Perimenopause commonly lasts 4–8 years.

During this phase, oestrogen and progesterone levels fluctuate rather than decline steadily. These fluctuations affect systems involved in:

energy regulation

sleep quality

mood and anxiety

cognitive function and brain fog

stress response and recovery

Research suggests that 70–80% of women experience symptoms during perimenopause, and many of these are psychological or cognitive — not just physical symptoms like hot flushes.

As hormonal patterns change, the body’s physiological resilience to stress can decrease. This means that even if work and life demands stay the same, coping and recovery may feel much harder.

For many women, this is the point where ongoing stress tips into a more serious or prolonged exhaustion — not due to weakness, but due to biological change.

Why burnout and perimenopause are often confused

Awareness of perimenopause is growing, but many women still reach this life stage without clear information about what it can feel like.

As a result, midlife fatigue is often explained as burnout alone — especially when work is demanding and routine blood tests fall within reference ranges.

What is frequently missed is how hormonal transition can amplify stress, reduce recovery capacity, and intensify burnout symptoms.

A more complete way of understanding midlife fatigue

For many women, the most accurate explanation isn’t burnout or perimenopause — it’s both.

Work stress may be the trigger.

Perimenopause may lower resilience.

Together, they can lead to fatigue, emotional depletion, and a sense of crisis.

Understanding this interaction often brings relief — because it finally makes sense.

What to explore with your GP

If fatigue, low mood, or burnout symptoms aren’t improving with rest or stress reduction alone, it may help to explore whether other factors are contributing.

Some women choose to ask about:

whether perimenopause could be relevant, even with regular cycles

whether iron status, thyroid function, or key nutrients have been reviewed

how stress and hormonal changes may be interacting

These conversations don’t require certainty — just clarity.

If this resonates

If you recognise yourself here, you’re not imagining things — and you’re not failing.

Burnout can be real. Perimenopause can be real. And sometimes, the combination is what turns pressure into exhaustion.

Understanding that context doesn’t solve everything — but it often changes what happens next.

Low Ferritin or Burnout? Why Iron Deficiency Is Often Missed

Low ferritin symptoms in women include fatigue, brain fog and low mood — even with normal haemoglobin. Learn why iron deficiency is often missed.

For many women, long-term fatigue is explained as burnout.

Work is demanding. Life is full. Recovery feels harder than it used to. Burnout often seems like the most reasonable conclusion.

But in a significant number of cases, exhaustion is not only — or not primarily — about stress.

It is linked to low ferritin, a sign of depleted iron stores that is frequently overlooked when haemoglobin levels are still normal.

When “normal” iron results don’t match how you feel

Iron status is commonly assessed using two markers:

Haemoglobin, which reflects whether there is enough iron to make red blood cells

Ferritin, which reflects iron stores — the body’s reserve

Many laboratories list ferritin values from around 20 µg/L (and sometimes lower) as “normal”.

When haemoglobin is normal and ferritin falls within this range, women are often reassured that iron deficiency is not the issue.

However, for many women, low ferritin symptoms appear well before anaemia develops.

Clinically, a large proportion of women do not feel well until ferritin levels reach around 50 µg/L or higher.

Iron deficiency without anaemia (IDWA)

Iron deficiency does not begin with anaemia.

There is often a prolonged phase where:

ferritin is depleted

haemoglobin remains within range

symptoms are already present

This is known as iron deficiency without anaemia (IDWA).

Because haemoglobin is normal, iron deficiency may be ruled out — even though iron-dependent systems throughout the body are already affected.

This is one of the main reasons low ferritin symptoms in women are missed.

Low ferritin symptoms in women that are frequently overlooked

Many healthcare providers are trained to recognise anaemia, but fewer are trained to recognise iron deficiency without anaemia.

As a result, symptoms are often attributed to stress, burnout, or mental health rather than low iron stores.

Common low ferritin symptoms in women include:

persistent fatigue or exhaustion

brain fog or poor concentration

low mood, anxiety, or apathy

reduced exercise tolerance

shortness of breath on exertion

dizziness or light-headedness

physical heaviness or weakness

hair shedding

frequent or lingering infections

These symptoms strongly overlap with those of anaemia — despite haemoglobin remaining normal.

Why low ferritin affects more than energy

Iron is often described as being important for oxygen transport, but its role in the body is much broader.

Iron is involved in:

cellular energy production

cognitive function and mental clarity

neurotransmitter activity related to mood and motivation

immune system function

This is why women with low ferritin often report brain fog, poor stress tolerance, low motivation, and frequent coughs or colds — even without anaemia.

When iron stores are depleted, the body may struggle to support multiple systems at once.

Why low ferritin is so often missed

Low ferritin is frequently missed because:

reference ranges are broad and symptom-blind

haemoglobin is prioritised over iron stores

symptoms are explained by lifestyle or stress

iron deficiency is only considered once anaemia appears

As a result, women may be told everything is “normal” — while continuing to feel unwell.

Over time, many adapt to functioning below their baseline, until exhaustion becomes severe enough to resemble burnout.

When burnout and low ferritin coexist

For many women, the question is not low ferritin or burnout — it is both.

Work stress increases energy demands.

Low ferritin reduces the body’s capacity to meet them.

Together, they can lead to:

reduced resilience

prolonged recovery

fatigue that does not resolve with rest alone

In this context, low ferritin does not replace burnout — it lowers the physiological buffer, making burnout more likely and harder to recover from.

What to explore with your GP

If fatigue or burnout symptoms persist, it may be helpful to explore iron status more closely — even if haemoglobin is normal.

Some women choose to ask:

what their ferritin level actually is (not just whether it’s “normal”

whether symptoms could reflect iron deficiency without anaemia

how ferritin results are being interpreted in relation to symptoms

whether ferritin levels around 20 µg/L are sufficient for optimal function

These conversations don’t require confrontation — just informed curiosity.

Why this understanding matters

When low ferritin is missed, women may spend years trying to improve their mental health when the problem is at least partly in the body — or, physiological.

Recognising low ferritin symptoms in women:

reduces self-blame

provides clarity

and often changes the direction of care

Burnout can be real.

Iron deficiency can be real.

And sometimes, addressing depleted iron stores is what finally allows recovery to begin.

Reference:

Cappellini MD, Musallam KM, Taher AT. Iron deficiency without anaemia: a diagnosis that matters. European Journal of Haematology. 2020.

Available at: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9692751/

Burnout, Iron Deficiency, and the Part of the Story I Was Missing

Long-term exhaustion isn’t always burnout. A personal story of missed iron deficiency, low ferritin, and what finally explained years of fatigue.

For a long time, I believed I was simply tired in the way adults are tired. The kind of tired that comes with work, children, responsibility, and getting older. I didn’t think something was wrong — I thought this was just life now.

But looking back, I can see how far from normal it really was.

I would wake up in the morning already exhausted, even after ten hours of sleep. I relied heavily on coffee just to get through the day, hoping each cup might finally do something. By late afternoon — still at work — the fatigue would hit hard. No amount of caffeine could touch it. My body felt heavy, my head foggy, I had hair loss and sometimes dizziness, and I was counting the minutes until I could go home.

I’d get through the evening routine with the kids, put them to bed, and then crash myself — far earlier than I wanted to. Evenings disappeared. There was no space for friends, no energy for hobbies, no exercise, no time for the basic life admin that quietly piles up when you’re always depleted. Everything became about getting through the day.

At some point, I started to accept this as my new normal.

I told myself it was my age. That it was life with kids and work. That maybe this was just how things would be from now on — permanently tired, permanently running on empty. What made it confusing was that I wasn’t neglecting myself. I wasn’t drinking excessively. I ate a healthy diet. I exercised when I could. I was doing all the things you’re supposed to do to “recover.”

And yet, nothing changed.

When people asked how I was, I said, “I’m fine.” Not because I was fine, but because explaining that level of exhaustion felt impossible. And because I didn’t want to hear the well-meaning responses: “Just take it easy,” or “It’ll get better when the kids are older.” I was already doing everything I could, and none of it was making a real difference.

There were moments that stayed with me. After returning to work, a colleague told me he wouldn’t bring me into his team because he assumed I’d just burn out again. Others seemed to think I was exaggerating how tired I was. That was hard to swallow — not just the fatigue itself, but the sense that it was becoming part of how I was seen.

Did I doubt myself? Yes and no. Part of me resigned myself to this being normal. But another part — quieter, persistent — kept wondering whether there was more to it. That’s why I kept reading, searching, and doing blood tests on my own. I didn’t have anyone guiding me through that process. I didn’t even know who could.

The real turning point came in an unexpected way: a Facebook group called The Iron Protocol. It sounds almost absurd now, but that group changed everything.

What I learned there was that the lower limits used for iron stores — ferritin — are often far too low to support good health. To feel well, ferritin typically needs to be around 50 µg/L or higher. Yet many lab ranges list anything above 20 µg/L as “normal.”

When I looked back at my own results, I was stunned. For five years, my ferritin had hovered between 20 and 30 µg/L — sometimes dropping even lower. No one had flagged it as a problem. In fact, it had likely worsened over time, partly due to endurance running and partly because I’d almost become vegetarian in an effort to improve my health.

Once I started appropriate treatment, the change was dramatic. Within about three months, my energy returned to what felt like normal. Not superhuman — just functional. Capable. Present.

And that’s when the anger hit.

I was angry that I’d been left unwell for so long. Angry about the years of unnecessary struggle. Angry about the time lost — time I could have spent feeling better, being more present with my children, living more fully. I hadn’t expected that grief, and I didn’t really know where to put it. It just felt deeply unfair.

Around that period, I had already left my job due to “burnout” and had retrained as a lifestyle coach and nutritionist. Food and health had always mattered deeply to me. But about six months ago, something clicked. I realised I could be the person I had needed — the one who helps women make sense of what’s happening when the burnout label doesn’t explain everything.

This wasn’t just my story. A close family member experienced something similar: severe iron deficiency, burnout leave, and eventually being pushed out of her job. I started seeing the same pattern again and again — women struggling, labelled, and left without real answers.

That’s what motivates me.

I don’t want women to stay stuck believing they’re broken, weak, or simply “not coping.” I don’t want exhaustion to quietly shrink lives while everyone assumes it’s inevitable. I believe there is often more going on — and that asking better questions sooner can change everything.

I used to believe my tiredness meant I was just getting older.

Now I believe it often signals an imbalance or dysregulation in the body.

If you’re reading this and you feel dismissed, I want you to know this: you’re not imagining it. There are people who can help. There is information out there. And you are allowed to keep asking questions — even the ones that feel obvious or “stupid.” No question is stupid when it comes to your health.

Keep advocating for yourself. You deserve answers.

The Hidden Biology Behind "Burnout": Why Mid-Career Women May Be Getting the Wrong Diagnosis

Rising burnout rates in women may mask iron deficiency, thyroid dysfunction and perimenopause. Why mid-career fatigue is often misdiagnosed.

Sarah*, a 41-year-old marketing executive, spent two years being treated for burnout. She'd tried therapy, meditation apps, and even a sabbatical. Nothing helped. It wasn't until a routine blood test revealed critically low iron stores that the pieces fell into place. Within months of proper treatment, her "burnout" vanished.

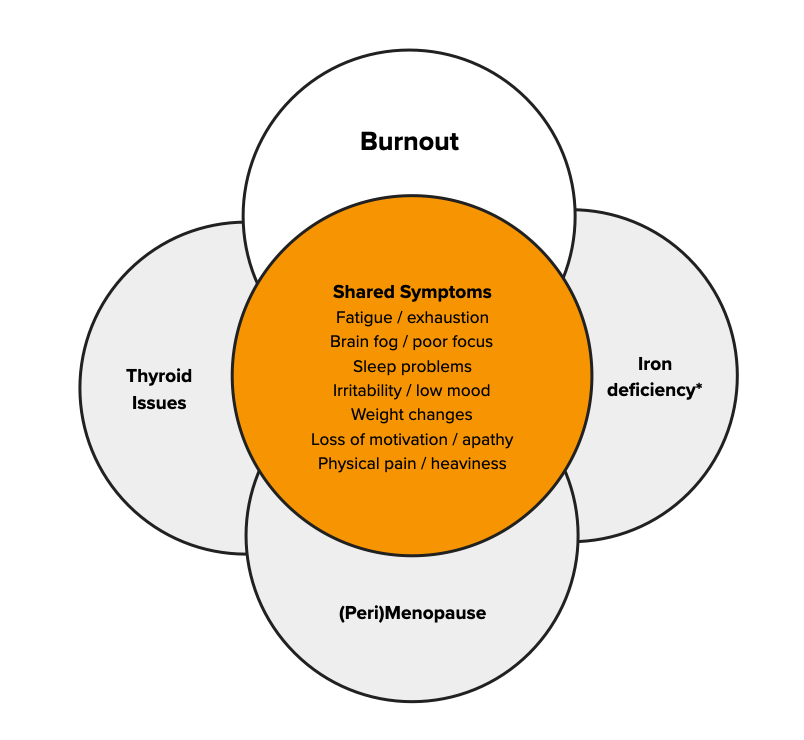

Sarah's experience highlights a concerning gap in how we diagnose fatigue in mid-career women. While workplace stress is real, there's growing evidence that biological conditions—particularly iron deficiency, thyroid dysfunction, and perimenopause—are being missed or diagnosed late, leaving women to struggle with treatable medical problems misattributed to psychological causes.

The Burnout Gender Gap: A Global Pattern

The scale of burnout among women is striking—and growing. In the Netherlands, burnout complaints surged from 11.3% in 2007 to 19.0% in 2023, with the increase particularly pronounced among women, those aged 25-35, and workers in healthcare and education. Swedish research reveals an even starker picture: 21.1% of women experience burnout compared to 12.8% of men, with women aged 40-49 showing the highest rates at approximately 25%.

Across North America, the pattern persists. In the United States, 46% of women report burnout compared to 37% of men—a gap that has more than doubled since 2019. A comprehensive analysis of 71 studies across 26 countries confirmed that women in healthcare professions endure significantly higher stress and burnout than their male colleagues. Even in China, female dental postgraduates show elevated rates of burnout, career choice regret, and depressive symptoms compared to male peers.

The burden is particularly heavy in Africa, where up to 80% of physicians in some countries report burnout, with women showing the highest scores. Among Moroccan oncology healthcare professionals, 61.5% experience severe burnout, with younger age and female gender identified as key risk factors.

Yet as burnout diagnoses soar, an uncomfortable question emerges: are we correctly identifying what's burning out—minds or bodies?

The Biological Triad

Iron Deficiency: The Misdiagnosed Epidemic

Iron deficiency affects 20-30% of menstruating women globally, yet its psychiatric impact remains dangerously underrecognized. In a Swiss study of 1,010 women diagnosed with iron deficiency, 35% initially received a different diagnosis—most commonly depression, burnout, anxiety, or chronic fatigue. These misdiagnoses led to unnecessary treatments and delayed appropriate care, leaving women symptomatic for months or years.

The mechanism is elegant but devastating. Iron is essential for oxygen transport, neurotransmitter synthesis, and cellular energy metabolism. When stores drop, cognitive function plummets—even before anemia develops. Studies demonstrate that iron-deficient women score significantly lower on attention, memory, and learning tasks, with improvements occurring within weeks of iron repletion.

Standard screening often fails these women. Many have "normal" hemoglobin but critically low ferritin (stored iron). Research shows ferritin below 30 μg/L impairs cognitive function, yet diagnostic thresholds are often set at 12-15 μg/L—catching only severe cases. Among young women and those with prior anemia, diagnostic delays are common as physicians order multiple iron treatment cycles before investigating underlying causes.

Thyroid Dysfunction: The Subtle Saboteur

Large observational studies reveal that 4-7% of community populations in the USA and Europe have undiagnosed hypothyroidism, with four in five cases being subclinical (elevated TSH with normal thyroid hormone levels). The symptoms—fatigue, weight changes, mood disturbance, cold intolerance, cognitive fog—overlap substantially with burnout.

The diagnostic challenge is compounded by age and sex. Research from Japan examining over 23,000 adults found that approximately 50% of women aged 30-39 diagnosed with subclinical hypothyroidism using standard reference ranges had normal thyroid function when age- and sex-specific ranges were applied. For women aged 60-69, this overdiagnosis rate reached 78%.

Meanwhile, true thyroid dysfunction goes unrecognized because symptoms are nonspecific. Fatigue is attributed to poor sleep or stress. Weight gain is blamed on lifestyle. Hair loss is dismissed as aging. The diagnosis often comes years late—if at all.

Perimenopause: The Diagnostic Black Hole

Perhaps no condition is more systematically misattributed than perimenopause. Women experiencing new-onset psychiatric symptoms during the menopausal transition face what researchers call "diagnostic overshadowing"—their symptoms are misdiagnosed as depression, anxiety, or in women with pre-existing mental illness, as relapse.

The statistics are sobering. Studies show seven of the eight conditions on the Patient Health Questionnaire depression scale (PHQ-8) can be caused by perimenopause or menopause, yet 25% of women aged 50-65 have never been told by their doctor that they're in this transition—even when 92% experienced menopausal symptoms in the past year.

Diagnosis is complicated by timing. Psychological symptoms typically precede physical ones by up to five years. A woman in her early 40s experiencing anxiety, irritability, insomnia, and cognitive changes may not yet have hot flashes or irregular periods—the "classic" signs clinicians expect. Research from multiple large cohort studies demonstrates that women with no history of depression are twice as likely to develop depressive symptoms during perimenopause, yet this knowledge hasn't translated into clinical practice.

The Interactive Triad: Why These Three Conditions Cluster

These conditions don't merely coexist—they interact. Iron deficiency impairs thyroid hormone metabolism and may worsen thyroid dysfunction. Perimenopause increases iron requirements while many women experience heavier menstrual bleeding, depleting iron stores. Thyroid dysfunction becomes more prevalent during the menopausal transition, with fluctuating estrogen affecting thyroid function.

A woman with all three conditions faces a multiplicative effect on symptoms. Her fatigue isn't just additive—it's synergistic. Her cognitive impairment compounds. Her emotional regulation crumbles. And when she seeks help, she's told she's burned out.

What Should Be Tested?

For women presenting with burnout symptoms, comprehensive evaluation should include:

Complete iron studies: Hemoglobin, ferritin, transferrin saturation, and iron. Ferritin below 30 μg/L warrants treatment even if hemoglobin is normal.

Comprehensive thyroid panel: TSH, free T4, free T3, and thyroid antibodies (TPO). Use age- and sex-specific reference ranges.

Reproductive hormone assessment in women 35+: FSH, estradiol, and consideration of cycle patterns to evaluate perimenopausal status.

The Path Forward

This isn't about dismissing psychological factors or workplace stress. Both are real, prevalent, and deserve attention. But when we default to psychological explanations for women's exhaustion without ruling out treatable biological conditions, we fail them twice—once by missing their diagnoses, and again by implying their suffering is somehow less "real."

Sarah's journey from misdiagnosed burnout to proper treatment isn't rare—it's disturbingly common. How many other "burned out" women are actually iron-deficient, hypothyroid, or perimenopausal? Until we routinely test for these conditions, we won't know. But the evidence suggests the number is substantial.

The question we should be asking isn't "Are you burned out?" It's "What's burning out—your mind or your biology?"

For Sarah, and countless women like her, the answer changed everything.

*Name changed to protect privacy

References

Alqahtani N, et al. (2019). Economic burden of symptomatic iron deficiency – a survey among Swiss women. BMC Women's Health, 19(1):38.

Cappellini MD, et al. (2020). Iron deficiency anaemia revisited. Journal of Internal Medicine, 287(2):153-170.

Hadine J, et al. (2024). Does menopause elevate the risk for developing depression and anxiety? Results from a systematic review. Menopause, 30(4).

Laurberg P, et al. (2021). Low awareness and under-diagnosis of hypothyroidism. Current Medical Research and Opinion, 37(12):2097-2106.

O'Brien KM, et al. (2023). Severe mental illness and the perimenopause. BJPsych Bulletin. PMC11669460.

Purvanova RK, Muros JP (2010). Gender differences in burnout: A meta-analysis. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 77(2):168-185.

Sholzberg M, et al. (2024). Diagnosis and management of iron deficiency in females. Canadian Medical Association Journal. PMC12237530.

Statistics Netherlands (2024). Trends in burnout complaints in the Netherlands 2007-2023. National Working Conditions Survey.

Yamada S, et al. (2023). The impact of age- and sex-specific reference ranges for serum TSH and FT4 on the diagnosis of subclinical thyroid dysfunction. Thyroid, 33(4).